This toolkit is one of the outputs from the Antislavery Knowledge Network (AKN), which between 2017-2023 supported 14 collaborative research projects through the UK’s Global Challenges Research Fund. Together this work examined the power of arts and humanities to address contemporary forms of enslavement by adopting community-engaged approaches.

The toolkit draws from insights and learnings from across the AKN and it was part of an exhibition showcasing all the projects, co-curated by a team led by Sophie Otiende, Allen Kiconco, and Chao Tayiana Maina, which included discussions of ethics and the value of different arts-based methods for engagement.

The toolkit was authored by Sophie Otiende following discussions between the curatorial team, and is currently hosted by the Collective Threads Initiative in partnership with the University of Liverpool.

For more information on the AKN partners and projects visit: https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/politics/research/research-projects/akn/

This is a simple tool that strives to help practitioners who are thinking about ethical storytelling. It highlights some of the things that practitioners in the anti-slavery or -human trafficking sector need to think about to be more ethical. The tool was inspired by work done by Antislavery Knowledge Network’s partners. It suggests key principles and ideas drawing from AKN partners’ efforts to apply inclusive and participatory practices in their individual projects, but there is also a resources section that points to good practice and guidance from others in the sector.

Please note that context is important. Always relying on information from the particular context you’re working in and the people that you are working with is crucial. This requires us as practitioners and researchers to be consistently learning and using that knowledge to think critically about the ethical issues that come up.

There is no question that power plays a huge role in how we tell stories, who tells stories and ultimately whose stories are listened to. It is important as a storyteller embarking on storytelling to question the power dynamics that exist. These dynamics may exist as a result of:

At any point, if you are the one writing the story, you need to reflect on the power dynamics that give you the power to write the story and strive to mitigate that power through centring survivors’ voices.

How do we reduce/ check power dynamics?

Good, compelling storytelling requires resources. That may mean having good cameras, or specific skills like writing and editing and access to other technology. This is not always something that communities have at their disposal.

It is important to recognise that sometimes as a storyteller, your best contribution to a project might just be to give access to resources that participants or communities might not have had access to previously.

Here are some questions to guide you when thinking about resources in ethical storytelling.

When working with people with lived experience, it is important to think about trauma and avoid re-traumatisation. This is not always easy especially if the trauma narrative is at the centre of the storytelling project.

Here are some things to consider that can help when working with people who have gone through trauma.

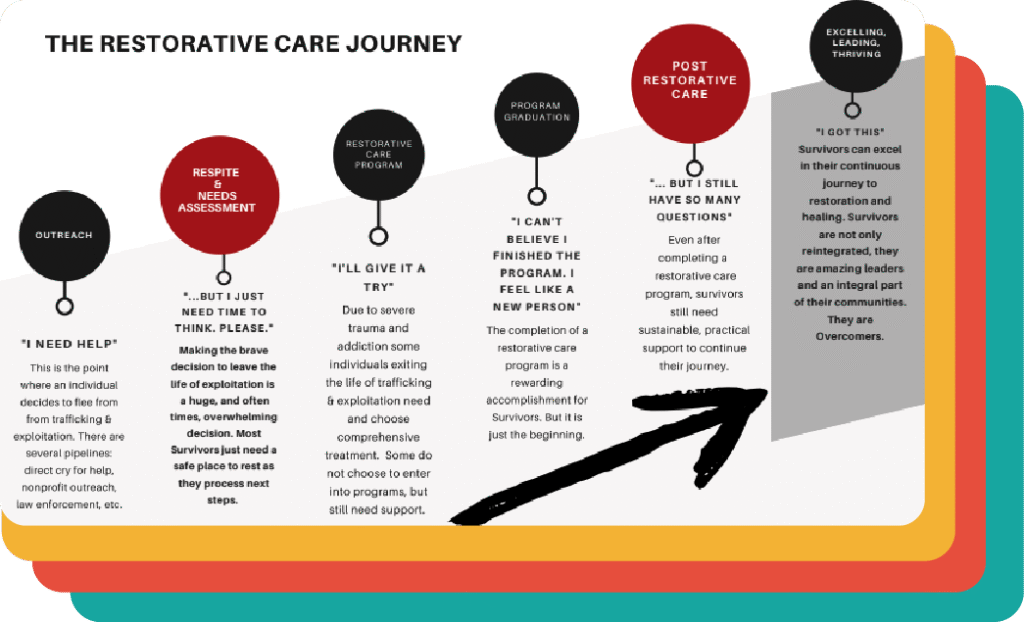

Discuss at what stage ( look at the diagram below) in the healing process survivors should engage in the project. This is extremely important when you think about informed consent. Only survivors/people that can freely consent should participate.

The diagram above was developed by survivor leaders from Twelve 11 Partners which is a survivor led organisation based in Austin Texas. It is important to note that sometimes this is a step by step process, and sometimes it’s not. The diagram is also based on survivor leaders that go through programs supported by non-profit organisations. The path might look quite different for those who don’t have access to support, or who access their support elsewhere.

It is important to note that different stages present different ethical issues when pursuing inclusion of survivors. Here are some tools from AKN Partners that can support you when thinking about safeguarding when working with survivors and vulnerable groups.

For further reading of safeguarding and equitable partnerships:

This report includes a summary of 3 case studies:

Most of the time while discussing ethics and storytelling, there is tendency to focus on the end product while neglecting the process. The question of ethics should be addressed throughout the process of storytelling. Storytelling is not an event but a process and for it to be ethical, an analysis of how ethics can be applied at each stage is important.

The three stages are:

This is the first part of storytelling and it lays the foundation for the outcome of the project. Being ethical has to start from the planning process all the way to the final product.

Here are some things to think about in the planning process:

During the process or implementation phase some key elements to consider are:

A crucial consideration throughout the process of any project is gaining informed consent. Some of the things to think about to ensure that this process is ethical include:

Project participants need to know about all the processes involved in the project of storytelling. For example, it’s very important to explain to participants about the editing process, if you are planning to do the editing and what that means and looks like. If the project will be distributed online, its important to discuss what that means in relation to consent and the limitations they have in case they want to withdraw that consent.

They need to understand the risks, the benefits, the people and organisations involved in the process. Some risks have been identified in preliminary research findings such as Survivors’ Experiences of Sharing Their Trafficking Stories Publicly. Provide resources for planning for and mitigating risks, such as those in the Survivor Storytelling Workbook.

After the active implementation phase of any storytelling project there are a further set of considerations:

Here are some resources from AKN Partners on the process of co-creation with survivors and vulnerable groups

Further Reading- while some of these tools are designed for research, the lessons identified can be used for a creative project

You can find more information on ethical storytelling, the importance of using stories, and policies on the use of images at the following links from other groups: